How can we use concepts of felt safety to increase emotional flexibility?

A friend recently asked me “Why are some people open minded and accepting of new ideas, while others get defensive or resistant any time something contradicts their current point of view?”

My answer started with the concept of felt safety and ended with summarizing regulatory capacity. It was likely more information than she was looking for, but when I finished she said “If everyone understood this, it could change the world.” I agreed.

Self regulation has the potential to change the world.

It starts with felt safety.

Felt safety is a perception.

It isn’t an objective measurement of actual safety, but instead, a judgment our body and brain make, based on unconscious physiological processes.

Understanding regulation starts with the safety tipping point: a valence based tipping point mechanism that is continuously working in the background of our brain’s functioning.

Occupational therapist Tracy Stackhouse has brought this safety tipping point terminology out of neuroscience research and into clinical pediatric therapy practice, deepening our understanding of felt safety and how it contributes to regulation.

Valence refers to having a quality of being positive or negative. This tipping point mechanism is always judging what is happening as being good or bad; pleasant or unpleasant; comfortable or uncomfortable; something we want to move towards (approach) or something to move away from (avoid).

The term “tipping point” describes how we are either tipped one way or another; there is no in between. Our brain only has two ways for perceiving our safety: safe or unsafe.

Our brain is always tipped one way or another: into a state of felt safety or a state of protection.

When we are tipped towards a state of safety we can explore, learn new things, and be adaptable. We can access our whole brain, including our cortex (the part of our brain that is responsible for language and logic). We are able to persist at hard things.

When we are tipped towards a state of protection the lower parts of our brain take over and we are much less able to use our whole brain. Our cortical functions of language, reasoning, and logical thinking are less available. We are less adaptable. We have difficulty learning new things. Being in a state of protection changes our muscle tone, the way we move, the way we breathe, and even our digestion.

This judgement of safe versus unsafe isn’t a conscious thought process. It is just a feeling that is based on our unconscious perception of safety. It is happening on a cellular and brain circuit level, and the implications are huge.

Imagine a young child who becomes very dysregulated when their sandwich is cut into squares instead of triangles. Their body and emotions are triggered into a highly activated state. Their heart beats fast, their muscles tense, their face gets hot, and their voice is loud and tight. They are objectively safe, sitting at their kitchen table, but their body perceives this situation as a threat.

Human brains don’t like change or unmet expectations, and perceive that as a lack of felt safety.

The same is true of an adult whose beliefs are being challenged or expectations are not being met. I’m not saying that it is exactly the same. Of course, as adults, our issues are bigger than the shape of a sandwich, our conflicts are more complex, and it can be much harder to discern which beliefs are truly right or wrong.

But the physiological mechanism underlying our response is the same.

Experiences of change, unmet expectations, psychological challenges, or anything that is perceived as a threat by the brain will trigger a protective response.

We might try to reason with the child who was expecting a sandwich cut into triangles by saying “It tastes the same either way”, but they are unlikely to change their mind or shift their behavior. That’s because in that moment they do not have access to logical thinking and sophisticated language. This phenomenon is known as state dependent functioning of the brain.

I find Dr Dan Siegel’s “flip your lid” analogy to be very helpful for teaching kids (and their adults) about state dependent functioning and how their brain works. I’ve described it in a previous blog, but it is worth repeating here:

If you hold your hand up in front of you, you can imagine that your arm is your spinal cord and the bottom of your palm is your brainstem. Now tuck your thumb into your palm and close your fingers over it. Your thumb (tucked inside) represents your amygdala and your brain circuits that are responsible for emotions; your fingers (curled over the top) represent your cortex, which is responsible for thinking, reasoning, and language.

When you are in a state of felt safety, your fingers are wrapped around your thumb. This represents your whole brain being connected and working together.

When we get triggered or activated into protection, by something happening around us or inside of us, we “flip our lid”. Your fingers open up, illustrating how we no longer have access to the smartest parts of our brain because we have lost our connection with the cortex.

Imaging studies confirm that when we are tipped towards protection we have less activity in our prefrontal cortex (the part of our brain that performs the function of responsible decision making) and an increase in activity in emotional circuits and lower brain structures responsible for protective responses.

When we are tipped towards protection we flip our lid. Our lower brain structures, which are responsible for protective responses, take over. We lose access to our cortex, which is responsible for language, logic, and reasoning.

The safety tipping point affects all of our regulatory capacities, including arousal regulation.

Arousal is another neuroscience concept that is helpful to understand when we consider the safety tipping point and other physiological processes that underlie behavior.

Arousal is the amount of energy available in our brain and body, in a given moment, to meet the needs of the situation. I call this neurological arousal “Activation”.

We teach kids that our Activation is the energy we feel in our muscles (whether they are tight or loose or somewhere in between), in our heart (beating fast or slow, hard or soft), our breath (moving short and fast or long and slow), our temperature, the rest of our body sensations and even our brain. We can notice our activation by tuning into our body sensations.

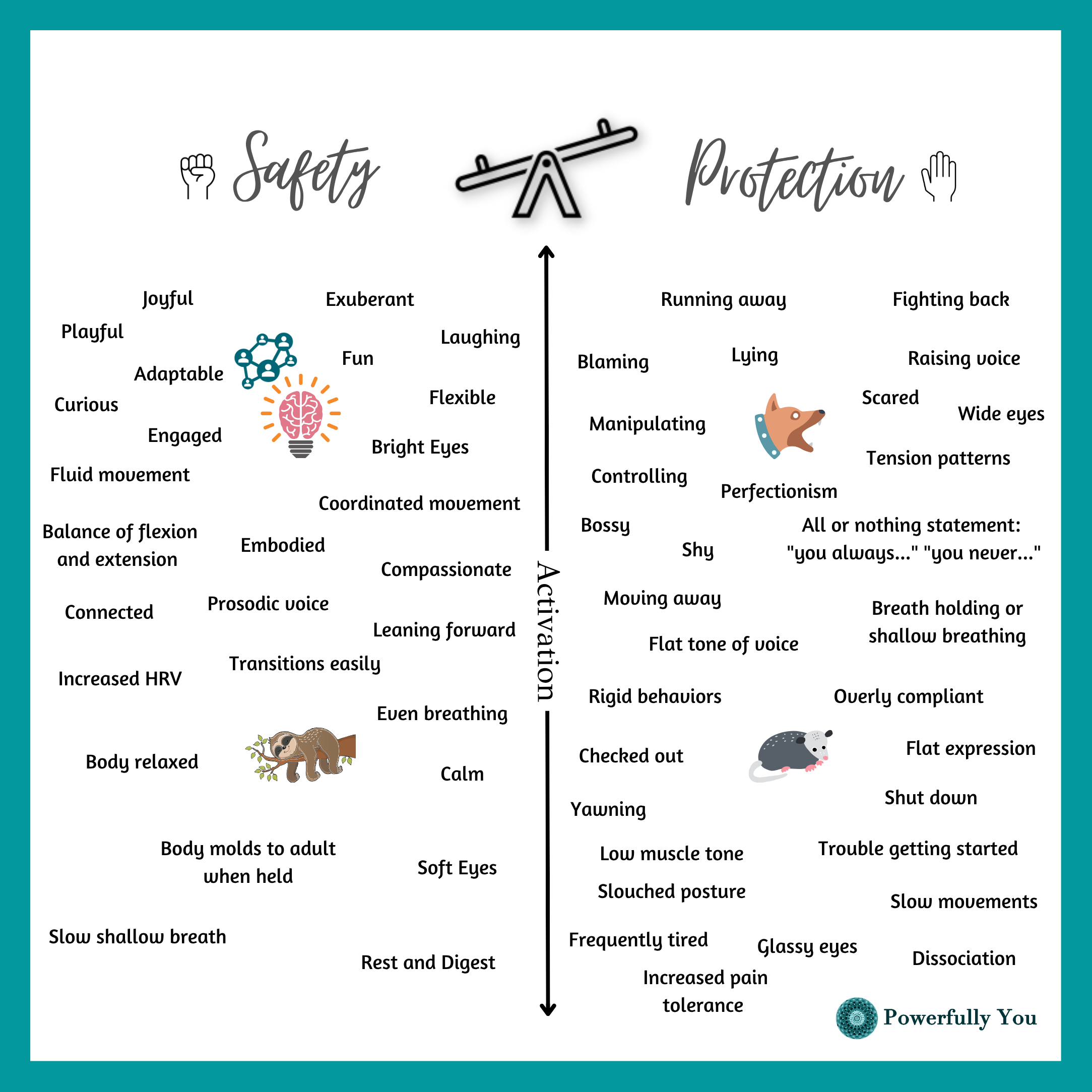

If we imagine representing arousal on a graph it might look like the continuum in the image below:

At the bottom of the graph we have low arousal/activation. That is how we might feel when we wake up in the morning and our brain and body are still moving slowly. When we are in this state of low arousal/activation it is not the best time to try to learn something new, or use our brain for the purposes of logical thinking and reasoning.

As our arousal increases we move into a window on the graph where our activation is more towards the middle of the range. In this window we are more alert, more adaptable, and can engage in learning and reasoning.

If we continue up the arousal continuum we move into a range of higher arousal, and in this range of activation we are more easily tipped into protection. The protective responses are coming from our autonomic nervous system. Protection can look like behaviors of mobilization (fight or flight), or immobilization (shut down or collapse).

We are most adaptable when our arousal is in the middle ranges. As we move toward increased arousal our protective responses are more likely to be activated; we are more likely to “flip our lid”by being tipped into protection, away from felt safety.

We instinctively know about this relationship between high arousal and safety tipping point. Adults watching kids engage in high energy play will often feel “on edge”, anticipating the crying, whining, or blaming that is likely to occur.

We are more likely to feel relaxed as we watch lower arousal play, because we sense that it is less likely to end up in emotional upset. The safety tipping point can be triggered in any range of arousal, but a child engaging in lower energy play is less likely to tip into protection.

High energy play is a great way for therapists to expand a child’s adaptability, but that is a topic for another blog.

Our own bodies are a good barometer for sensing when a child is moving away from felt safety towards protection. We might feel tension in our muscles, feel ourselves holding our breath, notice ourselves having all or nothing thoughts, or feel the need to control the child. Noticing protection behaviors in ourselves is a good indicator that the person we are with is tipped into protection, too.

We can also learn to notice behaviors and physiological signs that signal that a child is in a state of felt safety or state of protection.

One of the most important things we can do is recognize when a person is tipped into protection.

Just creating awareness in ourselves and recognizing that a child is responding from a state of protection can change the way we see them and interact with them.

Some examples of behaviors that tell us that a child is tipped towards protection are:

Blaming

Hitting

Running away

Shutting down

Being shy

Lying

Being overly compliant

Using all or nothing statement (like “ you always”or “you never”)

Being bossy or controlling

Perfectionism

Some examples of physiological signs of protection that we can observe are:

Flushing

Clenching/tight muscles (jaw, shoulders, fists are common places)

Breath holding or shallow breathing

Yawning

Lack of intonation in the voice/flat sounding speech

Darting eyes

Focusing on non relevant sounds in the environment

When we identify that a child is in a state of protection, it gives us information. It tells us that they don’t have access to cortical strategies (like using language, logic, and reasoning) to help them regulate. They need connection and coregulation to tip back towards safety.

Parents of teenagers would benefit from recognising that “all or nothing statements” are a sign of being tipped towards protection. Statements like “You always…”, “You never…”, or “I’m the ONLY one….” are a telltale sign that someone is not coming from a brain state where they can reason and use logic. They have flipped their lid.

When we hear those statements it is a signal that the child is tipped towards protection, and using reasoning and logic is not going to be useful until they have a sense of felt safety and are better regulated.

Therapists will benefit from learning to notice a child holding their breath or tightening their muscles. When we see that we can lower our expectations. We can shift our response away from talking and reasoning and move towards connecting with them and providing coregulation.

Changing the way we see people influences the way we interact with them. When we interact in a way that provides felt safety we are increasing their capacity for regulation and emotional flexibility.

As Robyn Gobbel, LCSW, says:

Changing the way we see people changes people.

If we could see everyone from a lens of felt safety, and offer connection and compassion, we would have a world of more flexible thinkers. Increasing our own capacity for self regulation is a great place to start!

For more on felt safety read my guest blog for Integrative Education

Resources:

Learn more about the work of Tracy Stackhouse at Developmental Fx

Learn more from Robyn Gobbel at her website