Self-Regulation Education: What works?

Self-regulation underlies everything that we do. Educators and parents are becoming increasingly aware of this foundational skill, that therapists have long known contributes to behavior, relationships, and academic success.

Social emotional learning curriculums offer ways to teach children concepts and tools to manage their own regulation. But can the skill of self-regulation be taught in a lesson? The answer is…it depends.

It depends on the child and their capacity to learn from a lesson that requires them to use cognition, language, and logic. It depends on the state of their nervous system at the time they are expected to learn and apply the information. And it depends on the way the information is presented and the relationship the child has with the presenter.

Let’s look at what works:

Self-regulation is the ability to adapt our neurological arousal, emotional state, motor activity, attention, and behavior to meet our own needs and the demands of the situation.

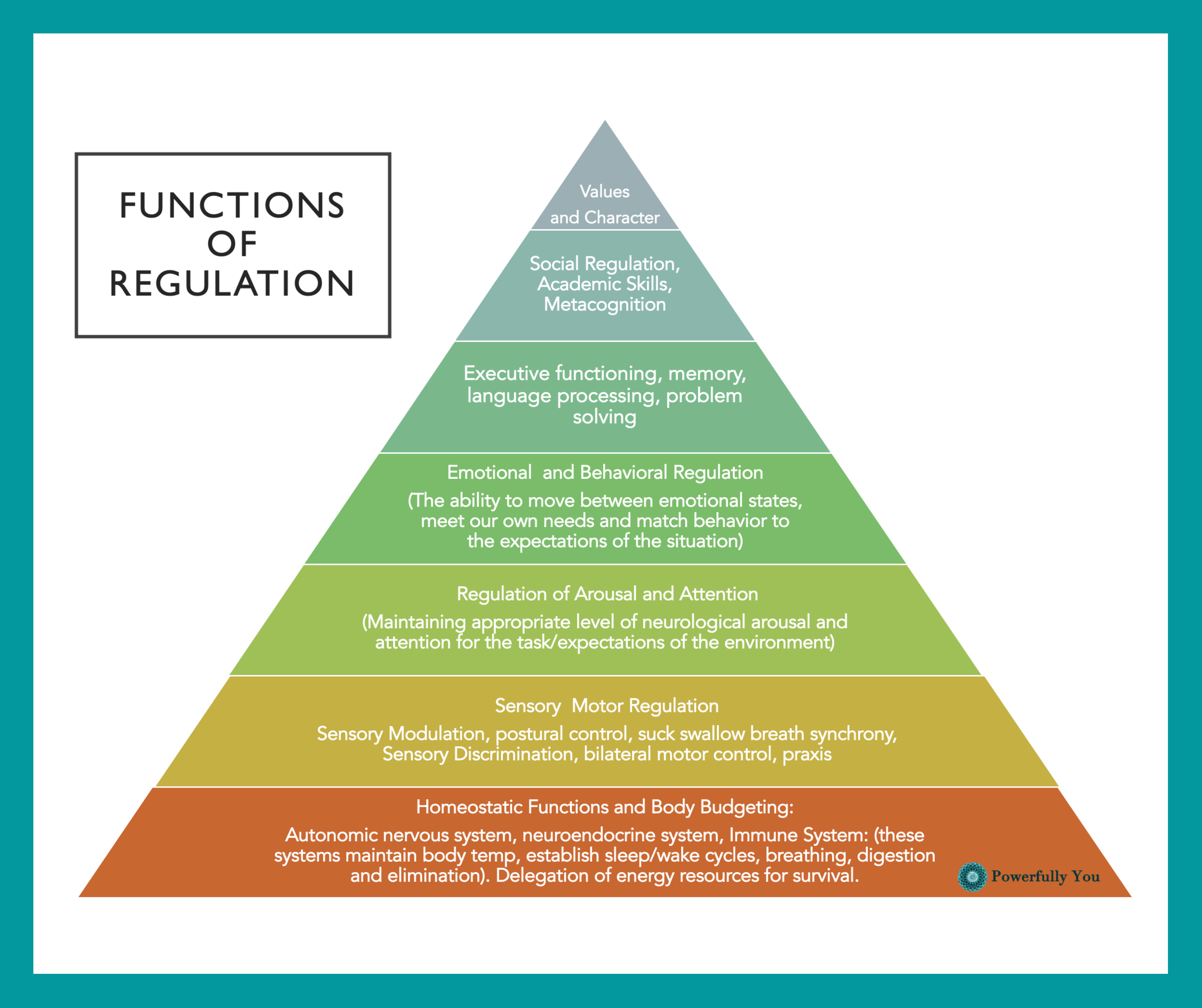

“Regulation” covers a wide scope of regulatory functions, ranging from homeostatic functions that happen at subcortical levels of the brain, up to prosocial functions that rely on cortical processing. Importantly, the cortical functions (at the top of the pyramid below) are dependent on regulatory functions happening through “lower brain” subcortical processes (lower in the pyramid) as a foundation for function.

Regulation is happening at all levels of the brain. It can be addressed used strategies that address top-down processing, and it can be addressed using strategies from the bottom-up. The best approach is one that integrates both bottom-up and top-down strategies.

A top down strategy uses language and logic to explain concepts. Bottom up strategies are interventions that would work on an infant; things like hugs, rocking, providing something to suck on or chew on, changing the environment, providing a snack. Those are all bottom up strategies for facilitating regulation, and we ALL need bottom up strategies sometimes, even as adults.

The key is discerning when one type of strategy is going to be more successful than another.

In the middle of this pyramid we have sensorimotor, arousal, behavioral, and emotional regulation. As occupational therapists, we are often targeting these regulatory functions in our treatment to bring about change at higher levels of functioning. By working on arousal regulation, we provide a foundation for social skills, academic performance, and character building.

Self-regulatory capacity can be affected at any level of the brain.

Physical supports (like getting enough sleep, eating well, and getting regular physical activity) work by providing a foundation for the homeostatic functions from the “bottom-up”.

Providing sensorimotor experiences that are upregulating and down regulating to the nervous system allow the child to match the activation needed for a particular situation.

Providing education about how the brain works and ways that we can think about our own thoughts can help develop “top-down” cortical regulation.

But top-down learning is dependent upon lower levels of functioning. And top-down learning, using language and concepts, is only available to us when we are in a regulated state.

Connection to others who help us feel safe is a prerequisite at all levels of self-regulation. As humans we are designed to need connection. In the absence of connections that help us feel safe in the moment (emotionally and physically), we are unable to learn to self-regulate.

Feeling safe is not something that can be objectively measured. Felt Safety is the subjective experience of the individual and it can shift from moment to moment. Our brains are wired to change the way they function when we are in a state of felt safety vs a state of protection. This “state dependent functioning” of the brain is a survival mechanism that moves energy resources away from cortical functions when we do not feel safe.

If we want to increase self-regulatory capacity using a curriculum, we first must address felt safety and facilitate a state of regulation that supports learning.

Providing the support that allows the child a sense of felt safety and regulation is called co-regulation. Co-regulation is the foundation for self-regulation. We must have many experiences of being reliably attuned to and co-regulated. Over time we internalize the regulation we receive through co-regulation as self-regulation. Our self-regulatory capacity does not fully mature until we are in our mid twenties!

Unreasonable expectations, judgement, and demanding compliance are all counterproductive to teaching self-regulation. Self-regulation is best taught through a lens of compassion and connection that values individual differences. A compassionate lens facilitates a sense of felt safety, providing a foundation for learning self-regulation.

Research has revealed many evidenced based ways of affecting self-regulatory capacity. They include:

Providing felt safety and compassion

Increasing interoceptive awareness

Increasing awareness of habits and fulfilling body budget needs

Increasing awareness of neurological and physiological arousal in the body and brain

Learning to use sensorimotor tools to upregulate and downregulate to match the situation

Practicing self-compassion

Building metacognition (the ability to think about our own thoughts)

All of these evidenced based concepts can be taught using a self-regulation curriculum, if a child is available to learn from top-down teaching.

Let’s look at each concept in a little more detail:

A compassionate lens validates everyone’s experience by teaching that we are all different and that’s a good thing! We all feel things differently in our body, prefer different tasks and experiences, and respond to inputs in our own unique way. Those individual differences make us better together. Imagine if we were all the same…we need those differences for our world to function well.

But sometimes our need to fit in, and our desire to help kids fit in, causes us to invalidate the experience of others. Adults with neurodiversity are currently speaking up about the harm caused by well meaning therapists who have taught them that they must fit in, and in the process invalidated their experience and damaged their sense of self.

As we build awareness and acceptance of everyone’s individual differences, we build an attitude of non-judgement: the foundation of compassion.

Awareness is also built through learning to notice our body sensations. Our internal body sensations, called interoception, are particularly important to understanding our emotional experience. Our body is always sending us signals about the condition of our body, whether we feel safe or unsafe, comfortable or uncomfortable, activated or deactivated. Using focused attention practices, we can learn to notice those body sensations that tell us about how we are feeling.

Research shows that practicing noticing body sensations over time builds capacity for emotional regulation.

Awareness of our “body battery” is another way to increase capacity for self-regulation. Our body battery is charged by:

Sleep

nutritious foods

regular physical activity

and connections with others who help us feel safe.

Increasing awareness of these body battery inputs can help an individual or their caregiver to notice how these habits affect regulation. Self-regulation is more accessible when our body battery is well charged.

We can also build awareness of the neurological and physiological arousal of our brain and body, otherwise known as our “Activation”. This summary of our body sensations is always telling us how activated we are in the moment, and whether our activation is a match or a mismatch for our needs and the situation we are in. Our brain is always receiving these messages, and responding automatically.

When we practice noticing those body sensations we can become more aware and have more control over our response. Building awareness of activation is a common practice in occupational therapy. Sometimes this awareness is built by noticing emotions, which are one kind of feeling. The other kind of feelings, body sensations, can be a more reliable foundation for understanding our own experience.

Teaching kids to notice their body sensations and how activated they are in the moment (based on their body sensations) will better prepare them to assess how tools work to upregulate or downregulate their activation.

Emotions are a summary of our body sensations, our perception of what is happening around us, and the predictions of what has happened to us in the past. Noticing emotions can be helpful, but noticing body sensations is a more reliable way of being aware of our own experience.

Often, adults are relying on outwardly observed behaviors as an indicator of the state of a child’s nervous system. Behaviors are not a reliable way of assessing activation. For example: A child who is overwhelmed might act out, but they might also shut down to deal with the overwhelm. A child whose nervous system does not feel activated enough to engage in academic learning might look disengaged or checked out to the observer, but they might also use motor activity and fidgeting to try to increase their own activation. The adult observing this may think that the fidgeting child needs to calm down (downregulate), when what their body really needs is input that is upregulating to help match their activation to the expectations of the situation.

Teaching children to notice their own activation is more reliable than making a judgement based on their behaviors or even their emotions.

Sensorimotor tools are something that all humans use to upregulate and downregulate their activation. We move our bodies to wake ourselves up, and to let off extra activation. We use our mouths to keep ourselves alert by chewing; we soothe ourselves by sucking, even as infants. Soothing touch by a loved one can downregulate our system, while cold on our skin can increase our alertness. Spicy foods can wake us up, sweet foods are typically soothing. Rhythmical music at a slow rate will calm us down, while a fast pace or arrhythmical beats will typically hype us up.

Giving kids an opportunity to explore many different sensory inputs, to notice how they affect their activation, and to determine which ones are most effective for them is a great way to increase their capacity for self regulation.

When they engage in this activity with other kids or caregivers, they have an opportunity to see how everyone is different which helps to develop empathy for the experience of another person.

Connection is a biological imperative. When connection activities are built into a curriculum, the capacity for teaching self regulation is greatly enhanced.

Teaching caregivers and adults the value of connecting with kids, and teaching kids ways of connecting with others, builds the capacity of the subcortical structures of the brain. Simple cooperative activities can have a huge impact.

The ability to have self-compassion is thought of by many as the highest level of self-regulation. When we can be aware of our own experience without judging ourselves, and learn to speak to ourselves kindly, we are providing ourselves a sense of felt safety. When we take this one step farther and notice that our experience is likely something that everyone in the world feels sometimes, we increase our sense of common humanity and connection to something bigger than ourselves.

Self compassion can be taught explicitly in a lesson, by engaging in excercises that build that capacity. Self compassion can also be modeled in the language and emotional tone of a curriculum. The skill of self compassion is most effectively built through compassionate relationships with others who “wire in” a compassionate view of ourselves.

Learning to notice what we are thinking, a skills called metacognition, and questioning our own thoughts is an advanced skill that requires the cortex to work very hard to downregulate the lower brain structures. It is a slower route to self regulation, but when practiced regularly in the context of felt safety, it can have significant effects. This inquiry-based thinking can be taught by a facilitator who is trained to do so effectively, with non judgement and compassion.

We can increase self-regulatory capacity through metacognition (thinking about our own thoughts).

All of these practices can be facilitated by a curriculum, with a child who is ready to engage in learning from a curriculum.

Regularly engaging in these practices with a supportive caregiver is what builds capacity.

There are many children who need a different approach to build the basics of self-regulation before a curriculum will be helpful.

Children with neurodiverse brains, developmental delays, or a history of trauma may need self regulation to be addressed in a way that doesn’t require a lot of cognition or require them to be regulated first. Remember, being regulated in the moment is a prerequisite for being able to learn using language and concepts.

All curriculums that teach directly to the child are top-down interventions. These can be useful for building bottom-up capacities (like noticing body sensations), if the child has enough capacity for regulation to engage in them and engages in the practices regularly.

If a child is unable to attain a level of regulation necessary for top-down learning, bottom-up strategies must be employed. It is beyond the scope of this blog to go into details of bottom up strategies, and we recommend seeking the guidance of a therapist trained in sensory, motor, and relational ways of building regulatory capacity.

Here is a list of some ways of they might address regulation with children who are not ready or able to engage in a curriculum:

Provide somatosensory soothing and coregulation

Meet their Body Battery needs

Facilitate the suck swallow breathe synchrony

Facilitate postural control in alignment

Address sensory defensiveness

Evaluate and address sensory modulation and sensory discrimination concerns

Facilitate mature motor patterns

Meeting a child where they are in their development is imperative to facilitating self regulation.

In summary:

A curriculum can be helpful when it is a match for the skills and needs of the child.

A curriculum can address a wide range of skills that underlie self regulation.

Approaching self regulation from an integrative perspective is the most effective way to increase a child’s capacity for self regulation.